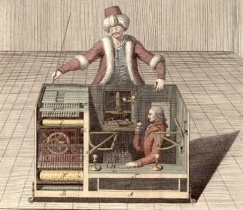

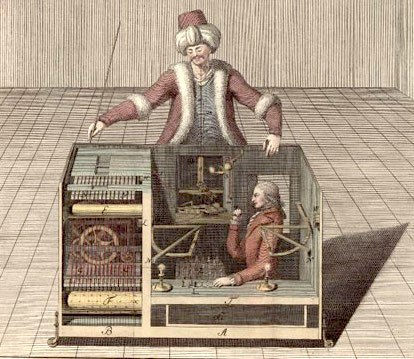

One of the ongoing discussion topics in the MSL is recruiting participants. We all carry out traditional lab studies, meeting participants in person in highly controlled circumstances, where we are confident participants can take part in experiments comfortably and without distraction. This practice has been a mainstay of psychological research for decades. However, working in a music department, we do not have access to a traditional participant pool of undergraduate students who take part in studies for course credit. One option that has become available to researchers in recent years is crowdsourcing. There are a number of platforms (for instance Amazon’s MTurk service), where people will complete ‘Human Intelligence Tasks’ for a fee (often known as microtasking). Tasks that can be crowdsourced in this way include tagging stock images for content, market research, app testing. The name MTurk is a reference to the Mechanical Turk chess playing automaton shown in the image – that was in reality a person hidden behind a curtain. Similarly, MTurk is used for tasks that we would expect to be completed by a computer, but in reality need human intelligence to be completed accurately.

Crucially for researchers, questionnaires or simple cognitive experiments can also be completed quickly and in bulk via crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing platforms allow for large amounts of tasks to be completed quickly, and so, unsurprisingly, researchers in several disciplines have turned to crowdsourcing as a recruitment tool for empirical research. Anecdotally, use of crowdsourcing platforms such as MTurk, Figure Eight (formerly known as Crowdflower) and Prolific is very much on the rise in academia. Indeed, according to at least one estimate (Stewart, Chandler, and Paolacci 2017) the number of studies in Cognitive Psychology that uses crowdsourcing is set to reach 50% in the next few years, a figure which seems surprisingly high. Our field has perhaps been a little slower to embrace crowdsourcing than other sub-disciplines within psychology, but crowdsourced studies are becoming more popular and their prevalence in social and behavioural sciences more broadly means that they are becoming hard to ignore. As a simple measure of the expansion of crowdsourced research in music science, the graph below shows the number of results for a Google Scholar search for “Music Psychology MTurk” for each year from 2005 (the year MTurk was launched) until 2018.

Alongside the core research studies we are running, several members of the MSL have developed an interest in crowdsourcing. In part, this interest is driven by a desire to make recruiting participants easier, but we are also hoping to adopt (or at least trial) what is becoming a major methodology in other branches of cognitive psychology, and importantly to broaden the geographic and demographic spread of participants who take part in our studies.

At first glance, crowdsourcing seems to offer a whole host of benefits to researchers. Quick data collection, a global participant pool, a more diverse selection of participants than is usually available for studies (Huff and Tingley, 2015). However, crowdsourcing also presents challenges and questions, some which are shared with other data collection techniques and some which are unique to crowdsourcing.

We wrestled initially with how we would know whether or not the data collected was sound: have participants fully understood the instructions? Are they fully engaged with the study? How can we as researchers check this? Music studies are particularly reliant on auditory attention and vulnerable to interference from outside noise.

Aside from the procedural questions, crowdsourced data collection is also bound by the same ethical guidelines that govern other empirical research. However, it is important to remember that, in the case of MTurk, participants are both volunteers and workers. Consequently, researchers have to offer a rate of pay that reflects the length of the task, the level of concentration needed, and that accounts for the fact that some participants may depend on online tasks for some or all of their income. Should we pay minimum wage, or more? If we agree a rate at or above minimum wage, whose minimum wage do we use? US (Federal or State), UK, or something else? How do we pay participants who start but don’t complete studies, or whose accuracy rates on tasks renders their data unusable. Is there such a thing as pay that is coercively high? All of these questions have to be answered against the backdrop of ethical principles and budgetary constraints. The ethics of crowdsourcing (and Amazon’s MTurk in particular) became the pivotal issue in whether or not our studies could proceed. Initially, some members of the department’s research ethics committee asked for clarifications on crowdsourcing, which resulted in a lengthy process of finding out more around research practices with crowdsourcing.

Surprisingly, despite the rapidly increasing prevalence of crowdsourced research, guidance on these questions is hard to find, in the UK at least. The British Psychological Society’s Code of Practice for Internet Mediated Research makes no mention of platforms such as MTurk, Crowdflower or Prolific. Likewise, few university departments in the UK provide guidance on these questions. Fortunately, within the body of research mentioned earlier, there is a small number of qualititive studies that address the question of what it is like to be an MTurk worker, what motivates them and what they want to get out of MTurk. A spinoff from one of these studies, Dynamo (Salehi et al., 2015), is a collective of MTurk workers who drew up a non-binding set of guidelines for academic requesters. We found that our research proposal met or exceeded many the expectations laid out in these guidelines, but that we needed to think through our responses to some of the questions raised above. Importantly, Dynamo and (Deng, Joshi, and Galliers, 2016) reminded us that there is an element of participating in a research study that goes beyond the financial transaction. Empirical research would not be possible without the contribution of participants, and it is important that as researchers we remember to demonstrate the same courtesies and gratitude that we show to in-person participants, even if we are using an online platform with sample sizes of potentially thousands. As well as the qualitative research and researcher guidelines, we spent a long time browsing the many online communities that exist for MTurk workers. MTurkers are active on Reddit and Slack as well as having dedicated sites such as TurkOpticon (hosted by University of California, San Diego), Turkerview and mturkcrowd. Browsing these communities gave us a good sense of what makes a good requester – not blocking participants, paying well and promptly, dealing with queries quickly and professionally, ensuring instructions are clear, and that participants understand the value in what they are doing. Our final piece of preparation was to enrol as workers/participants on both MTurk and Prolific and complete a handful of studies each to get a sense of what completing a study via these platforms entails. After all of this, we were able to present the ethics committe with a summary of our findings on crowdsourced research and we were given the green light to proceed. Despite the effort involved, this process was helpful in helping us clarify the issues for this study and in developing guidelines that will be helpful to other empirical researchers in the department.

So, having gone through lengthy rounds of debate on the ethics, finances and technical requirements necessary for crowdsourcing, and having piloted our studies with our MSL colleagues, we were ready to launch our studies. Research Friday (Thanks, Imre) had arrived. James’ study compared how emotional music and emotional images influences our evaluations of the emotional content of language. Imre’s study collected data about participants’ perceptions of consonance and dissonance in chords. George is seeking to use MTurk’s geographical reach to conduct a cross-cultural music perception study. The launch of James’ and Imre’s studies also provided an opportunity to compare the functionality of MTurk and Prolific.

Both platforms offer several benefits in common. Both have large participant pools and provide speedy results. On the down side, both come with quite a hefty price tag in terms of commission to the platform – 30% plus VAT for Prolific and 40% for MTurk. Both offer pre-screening facilities, for instance by handedness, age, level of education, geographical location and so on. Another useful feature is that these platforms integrate smoothly with data collection platforms such as Qualtrics and PsyToolkit. MTurk has an almost global participant pool. Prolific has a wide-ranging set of pre-screen questions, including Brexit views and which football team you support. Usefully for us, Prolific also has a subset of participants who are screened for their musical expertise.

Prolific seems to offer the advantage of being set up specifically with academic research in mind. So, it has native functionality for follow up or longitudinal studies, something lacking in MTurk – there are workarounds, but they are far from perfect. Also, Prolific makes it easy to exclude participants who have completed our previous studies to avoid bias in the results. Again, this is possible in MTurk, but requires a workaround. Prolific’s academic flavour has the added strength of being very participant friendly. Participants receive email invitations to complete studies, and on completion are asked if everything ran as expected.

Research Friday’s main event was the launch of James’ and Imre’s studies; George and Tuomas watched carefully, perhaps ready to spot any errors on the part of their more gung-ho collegaues. Imre received 100 responses within a couple of hours, and James received responses to 250 Anxiety screening questionnaires, leading to 35 completed experiments.

Although the quality of the data was mostly good in both experiments, there were a few responses that suggested a lack of engagement with the study (e.g. failed attention checks, always responding with the same answer or poor accuracy in the images/music/language task.) Overall, we found that Prolific offered a slightly better experience for researchers, and Imre was able to make use of its musical training pre-screening. MTurk was effective in sourcing a large number of participants quickly, but its lack of native support for a two-stage study made recruiting (and paying) participants for the second stage of the study slightly harder work than we would have liked. The detailed pre-screening features, the researcher and participant-friendly feel and the excellent integration with other platforms gave Prolific the edge over MTurk as a recruitment tool for research.

One issue that we still need to address is around the quality of data obtained via crowdsourcing. As researchers, we need to be confident about the data that we obtain via crowdsourcing. Broadly speaking, there are two important things to think about: 1) is it possible to capture the effect we’re interested in using crowdsourcing methods? and 2) how usable is the data? There are a number of ways that we can do this. The first is to insert simple attention checks, e.g. in a questionnaire we can ask participants to “click moderately in response to this question” to weed out participants who are clicking indiscriminately or always picking “strongly agree”. Another simple check is what happens when we eyeball the data – is there anything wildly strange about it. As all three of the studies that we’re running have quite sensitive perception components to them, one option we’ll be pursuing in the near future is to replicate large-scale MTurk studies with small-scale samples in the lab. In terms of the data we’ve collected already, James’ initial MTurk pilot was very successful, 96% of participants passed the attention check, and of the participants who completed the second phase, only one (out of 40) was removed from the data set as a result of a low accuracy rate. The more recent MTurk study was less successful in this regard – whether this was due to a slight change in the recruitment process (in the pilot, participants who progressed from screening to the experimental stage were contacted via a message a day or so after the screening; in the more recent experiment, participants who progressed to phase two were offered this chance immediately at the end of the screening questionnaire). Whatever the reason, a large proportion of participants (14 out of 49) fell below the required accuracy threshold.

On the other hand, Imre’s data was of very good quality overall. There was a clear correlation between low response times and random response patterns, so removing those participants who completed the experiment in less than 400 seconds provided an effective filter for outliers. Further removal of those participants who correlated negatively with the majority resulted in a 10% discard rate, meaning that 90% of the data was of very high quality. Moreover, the 3 instalments of data collection (full data N = 465) resulted in a perfectly balanced participant pool in terms of musical sophistication. The possibility to prescreen for muscianship is a huge pro for Prolific. Judging by the exchange of messages with some of the participants during the data collection, many were interested in the upcoming results and the study itself. It was obvious that the majority of participants were more interested in the task itself than the monetary compensation. What this boils down to is that both platforms provided good data, but both the MTurk and the Prolific data sets needed careful scrutiny to identify to weed out some responses that looked like they hadn’t been completed quite as they should have been. Prolific again had the edge here, but it remains to be seen whether this is because of the nature of the platform or because of the nature of the studies.

Overall, our foray into the world of crowd-sourced research has been a success thus far. There has been a steep learning curve, both in terms of managing the studies and also in navigating the mores of the crowd-sourcing world. The process has allowed us to develop the beginning of a lab policy on crowdsourcing that should help future studies with designing studies, clearing ethics, the nitty-gritty of running a study and how to try to maximise the quality of the data. We’ve collected some usable data that will form an important component of our current studies, but have also learned not to be complacent and expect that a few clicks will provide us with a large volume of high-quality data. As part of our battery of recruitment techniques, it is valuable and very fast, and offers access to a partcipant pool with a wide geographical spread. However, as noted above, crowdsourcing is a technique that has limitations, and despite its evident power, it is something that can complement – but not replace – traditional lab studies.

References

Deng, Xuefei, KD Joshi, and Robert D Galliers. 2016. “The Duality of Empowerment and Marginalization in Microtask Crowdsourcing: Giving Voice to the Less Powerful Through Value Sensitive Design.” Mis Quarterly 40 (2). Society for Information Management; The Management Information Systems …: 279–302.

Huff, Connor, and Dustin Tingley. 2015. “‘Who Are These People?’ Evaluating the Demographic Characteristics and Political Preferences of Mturk Survey Respondents.” Research & Politics 2 (3): 2053168015604648. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168015604648.

Salehi, Niloufar, Lilly C Irani, Michael S Bernstein, Ali Alkhatib, Eva Ogbe, Kristy Milland, and others. 2015. “We Are Dynamo: Overcoming Stalling and Friction in Collective Action for Crowd Workers.” In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Acm Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1621–30. ACM.

Stewart, Neil, Jesse Chandler, and Gabriele Paolacci. 2017. “Crowdsourcing Samples in Cognitive Science.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 21 (10). Elsevier: 736–48.

Really interesting blog, thanks! I’ve just run my first three studies through Prolific and agree with you that it works really well for music studies, and the ability to interact with the participants (e.g. to clarify data that looks unusual, check details) and to get interactions from them (for mine also talking about how much they enjoyed the study, usually!) is great. We ran one of the studies 50% from in-person lab participants and 50% through Prolific and haven’t found any significant differences in the pattern of results, which is also encouraging.

LikeLike

Sounds like a good way of checking whether Prolific samples are responding like lab samples for your paradigm! How did you find Prolific in terms of setting up your study/stimuli? (Just asking as I’m considering using it for my next research idea).

LikeLike

Thanks – we’re looking in quite a bit of detail as how our experimental data compares across three samples: lab, prolific and ‘traditional’ web recruitment (email lists, social media etc). We’ve found differences between the lab and traditional web samples, but much less difference between the lab and prolific samples. We’ve also had some really positive and interesting responses from participants.

LikeLike