Insight from a pre-registered study published in the Music Perception journal

When starting out my music psychological research a good ten years ago (can’t believe I’m writing this!) I was interested in the question of whether the smallest building blocks of musical harmony, namely single isolated chords, could convey emotions to listeners in a robust and consistent way. For this end we (together with Professor Tuomas Eerola) designed a straightforward experiment that demonstrated conclusively that common tonal chords do indeed convey distinct emotions to both musicians and non-musicians, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that since establishing this ‘ground truth’ most of my research has been concerned with trying to unravel whether these emotional connotations have biological roots in how the human auditory system makes sense of acoustics, or if these affective responses are driven purely by learning in the form of enculturation (or possibly through a combination of these two extremes).

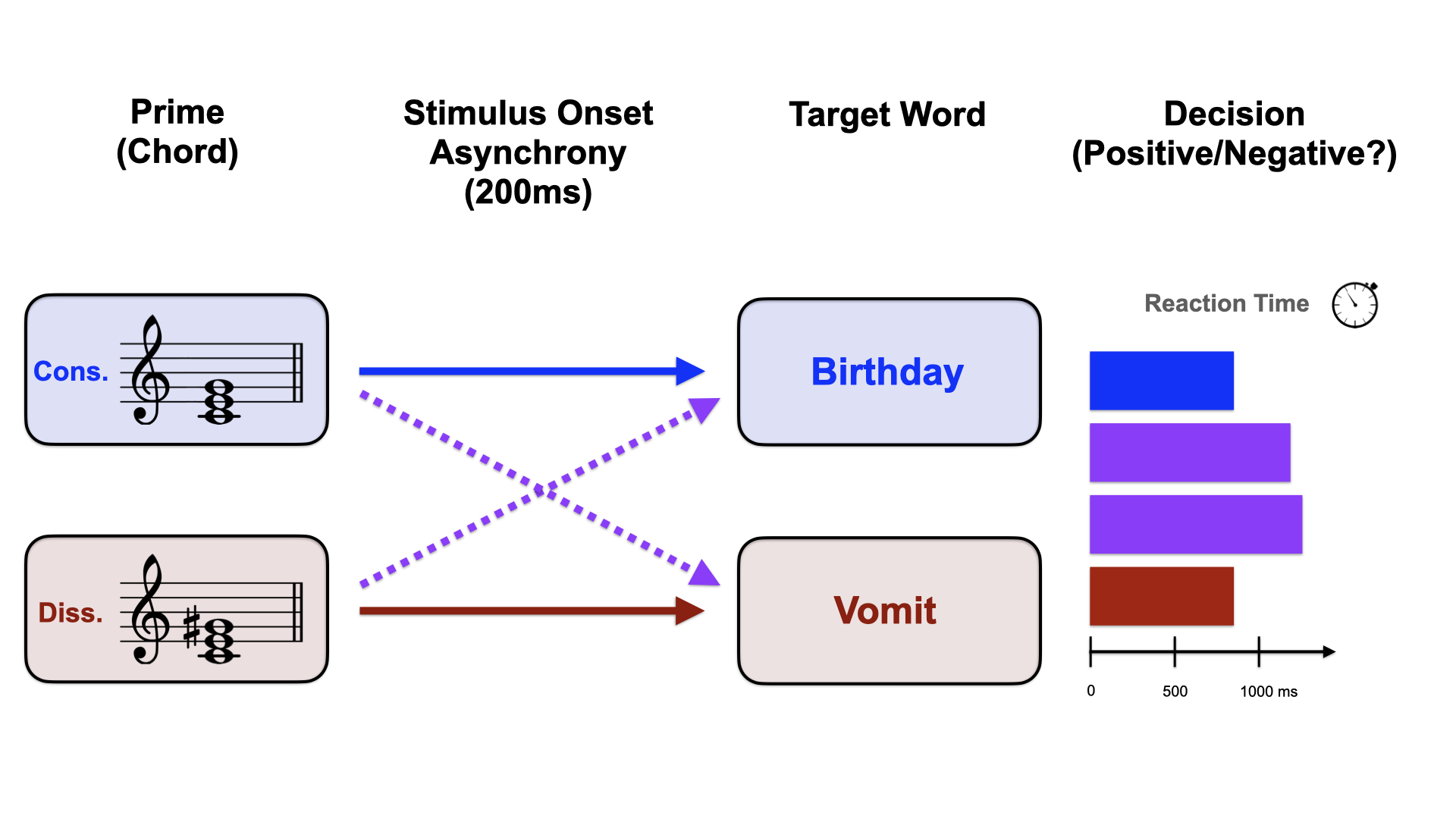

A very useful method to dig deeper into the underlying mechanisms behind emotional connotations to musical chords is a method called ‘affective priming’. Borrowed from social and cognitive psychology, it offers an objective and automatic measure of affective processing and it bypasses many of the obstacles related to semantics present in mere self-reports. It essentially brings some much-needed objectivity to a question that is notoriously prone to armchair theorising and (over)generalising without very much data. The affective priming method consists of two stimuli (the prime and the target) presented in quick succession. The extent to which the first (prime) stimulus influences responses to the second (target) stimulus is indexed by a reaction time and an accuracy rate. Target stimuli are typically evaluated more quickly and accurately when preceded by a prime of the same affective category (known as congruence) compared to when preceded by one of the opposite category (known as incongruence). The useful thing about the affective priming method is that it taps into unconscious, automatic responses. The participants simply do not have time to consciously consider their responses: if a preceding prime’s emotional quality spills over to the ensuing target word’s classification speed and accuracy, this is taken as evidence of the prime’s (in this case a chord) positive/negative emotional charge.

The affective priming method has been used only very sporadically to investigate harmony perception in the last 20 years; however, together with my colleagues here at Durham University we have been implementing this method quite regularly in recent years to rigorously and methodologically test theories of which acoustic/cultural predictors drive automatic responses to intervals and chords. Rather surprisingly our study on intervals (lead by our hard sciences expert James Armitage) demonstrated that pairs of intervals that carry quite specific cultural conventions in terms of positive vs. negative emotions (e.g., perfect fifth vs. tritone, major third vs. minor third, major sixth vs. minor sixth) do not influence target word processing. Instead, in intervals, influence on target word processing is driven exclusively by contrasts in acoustic roughness (i.e., the jarring sound quality that arises when musical pitches are so close together that the inner ear cannot fully resolve them; this acoustic roughness phenomenon has been demonstrated to influence chord perception also across cultures). When the contrast in acoustic roughness is large, the interval stimuli starts influencing the categorisation of target words in the expected manner (high roughness in dissonant intervals resulting in faster categorisation of negative words and vice versa). This curious finding got us thinking whether affective priming in chords would be driven by this same roughness contrast too: after all, previous studies on consonance/dissonance using the affective priming paradigm had all been using exclusively acoustically rough chord stimuli.

There were a few aspects on closer look that got us to hypothesise that intervals may well be a special case and that chords would not follow this congruence pattern driven exclusively by contrasts in acoustic roughness. First, intervals are heard fairly infrequently in isolation in actual music and are hence less familiar compared to chords which are positively ubiquitous. Second, chords contain more acoustic information due to the higher number of pitches (intervals contain only two distinct pitches while chords contain three or more pitches). Third, major and minor triads have previously been shown to create positive/negative congruence in an affective priming setting even with a negligible difference in acoustic roughness between them. In fact, we were so sure of our hypotheses of which chord pairs would create positive/negative congruence with target words that we decided to pre-register our study design and hypotheses beforehand in the form of a registered report in the Music Perception journal (the final report was published in Volume 43, Issue 3); my co-author Professor Tuomas Eerola has written in a related blog post in more detail about the concept of the registered report and its pros and cons). In our study we decided to test the very cornerstones of Western harmony, namely all four triads (major, minor, augmented, diminished) as well as a common trichord (suspended 4th) to map how the general population (listeners without musical expertise) perceive these chords in an affective priming setting. Let’s dig into the obtained results, chord pair by pair. You can listen to each chord below to refresh your memory on how they sound:

Major triad vs. Minor triad

A classic face off, the most famous of the emotional distinctions with regard to chords in Western music. As self-reports have shown a very robust mode of response of positive (major) vs. negative (minor) valence regardless of musical expertise we expected this to be reflected in automatic responses as well. To our great surprise however this pair did not deliver robust results in an affective priming setting. While on a self-report level non-musicians indeed consistently report perceiving this affective difference between major and minor, on closer inspection this difference according to musical expertise in the automatic responses is actually present in both previous affective priming studies (Steinbeis & Koelsch, 2011; Costa, 2013) with musicians showing much clearer automatic positive/negative congruence compared to non-musicians. In addition to serving as an important reminder that you cannot be too careful and meticulous when constructing pre-registered hypotheses based on previous research, this finding is definitely another point for the ‘nurture’ camp at the expense of the ‘nature’ camp in terms of the origins of the major/minor affective dichotomy: after all, if this automatic mode of response works robustly only with listeners who do have musical expertise but starts falling apart when tested on the general population, it is hardly corroborating theories according to which this affective distinction would be universal or based on spectral properties of human speech. Instead, it is in line with previous findings pointing to the strong role of learning and enculturation. While the cultural relativity of the major/minor affective mode distinction has for long been clear to many ethnomusicologists and musicologists (see an excellent overview in Tagg & Clarida, 2003), the ethnocentric universalism myth is surprisingly hard to put to bed within the realm of music psychology; we believe the current results provide another nail in the universalist coffin in terms of the major/minor affective distinction.

Major triad vs. Augmented triad

As hypothesised, this chord pair delivered clear affective priming results in line with low pleasantness ratings obtained through self-report data in previous experiments. Interestingly, the augmented triad’s dissonance is hard to pinpoint acoustically, and it has indeed been proposed that its dissonance in Western music is rooted in its low familiarity. As the augmented triad is present in the (harmonic) minor scale but not in the (most familiar) major scale, this chord’s negative emotional connotation stemming from its rarity has been effectively utilised by composers since the 19th century onwards, its use as an independent chord sonority pioneered by the forward-looking Romantic composer/virtuoso pianist Franz Liszt. It is notable that as the augmented triad’s dissonance is virtually impossible to explain convincingly purely with acoustics, our own cross-cultural research (fieldworked by cross-cultural research powerhouse Dr. George Athanasopoulos) into this question corroborates its likely cultural origin: the Kalash/Khow tribes residing in the remote valleys between Northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan with minimal exposure to Western music remarkably perceived this chord as something unfamiliar relative to their own music, yet as a sonority that is not inherently unpleasant.

Major triad vs. Diminished triad

This chord pair provided strong affective priming results as hypothesised (this pair was actually the most robust in terms of affective congruence among the current stimuli), and again in line with the low pleasantness ratings obtained through self-report data in previous experiments. This finding is not surprising given the long pedigree of its use to denote negative valence in Western music: the diminished triad’s negative affective connotation goes back further in music history than the augmented’s, its origins stretching back to early Baroque recitative at least. By the 18th century the diminished triad was already established as somewhat of a ‘cliché’ of horror and this connotation was only reinforced later in film music starting with early silent movies. While the diminished triad is consistently rated as less dissonant than the augmented triad, it seems to be a more effective marker of negative valence in the Western musical tradition. Presumably this is not only because the diminished triad is historically more established than the augmented but also because it is more familiar from actual music: the diminished triad is part of major and minor (harmonic) key harmonisations on the VII degree and minor (natural and harmonic) key harmonisations on the II degree, whereas the augmented triad is only present in harmonic minor keys (on the III degree). In other words, a dissonant chord used in both major and minor keys is arguably a more familiar marker of negative valence than a dissonant chord used only in (harmonic) minor keys.

Major triad vs. Suspended 4th

As hypothesised, this chord pair did not create affective priming results, in line with the high pleasantness ratings obtained through self-report data in previous experiments in response to the ‘sus4’ chord. On closer inspection this finding, although expected, is bit of a paradox. As previous research has established that the high roughness value of the major second interval creates automatic negative congruence, it is curious that adding just one pitch class to this interval to make the sus4 chord fools the ear into thinking that there’s nothing fishy about this particular sonority. As discussed in more detail in our pre-registered report, we have come up with a few tentative theoretical explanations for this finding. 1) It has been suggested that perceived roughness in a single chord may be mitigated by placing it in a (in this case hypothetical) contrapuntal context. The sus4 indeed contains tension stemming from an implied voice leading situation in the 4th degree’s need of resolution to either the minor 3rd or more typically the major 3rd; it is not impossible that this strong tonal pull indeed mitigates the sensory roughness of the major second interval within the chord through this implied motion. 2) It is always possible that the major second interval’s roughness is simply irrelevant in a chord that contains positive valence through associative learning: as the sus4 chord most typically resolves to a major chord in tonal music, it is possible that its positive valence is learned wholesale through this contextual association. 3) Finally, there exists a possibility that there is an interaction with the combined overtones of the individual fundamentals present in the sus4 chord that effectively softens the sensory roughness of the major second interval through perceptual fusion. What can already be concluded from the sus4 chord’s curious case is that the arising overall quality of a chord can evidently be different from the sum of its parts (as per the classic Gestalt notion of holistic perception).

So there we have it: single isolated chords do indeed create automatic emotional responses in the general Western population (without musical expertise), and our results imply a strong role of learning and cultural mediation in this. How and when exactly these emotional connotations arise and consolidate are questions for comprehensive further research.

A list of publications using the affective priming method by the Music & Science Lab:

Armitage, J., Lahdelma, I., & Eerola, T. (2021). Automatic responses to musical intervals: Contrasts in acoustic roughness predict affective priming in Western listeners. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 150(1), 551-560.

Armitage, J., & Eerola, T. (2022). Cross-modal transfer of valence or arousal from music to word targets in affective priming?. Auditory Perception & Cognition, 5(3-4), 192-210.

Armitage, J., Lahdelma, I., Eerola, T., & Ambrazevičius, R. (2023). Culture influences conscious appraisal of, but not automatic aversion to, acoustically rough musical intervals. PLoS ONE 18(12): e0294645.

Lahdelma, I., Armitage, J., & Eerola, T. (2022). Affective priming with musical chords is influenced by pitch numerosity. Musicae Scientiae, 26(1), 208-217.

Lahdelma, I., & Eerola, T. (2024). Valenced priming with acquired affective concepts in music: Automatic reactions to common tonal chords. Music Perception, 41(3), 161–175.

Leave a comment